One of the Hardy Folks who use the Dungeon

By Bill Clark

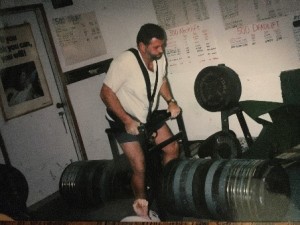

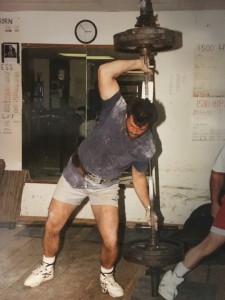

One of the hardy folks who use the dungeon-like facilities of Clark’s Gym to recuperate, recharge and keep Father Time at a distance, with or without a face mask, is Dave DeForest.

Dave turned 60 on February 3 and decided to join the elite ranks of those who, once past the age of 40, could earn a certificate for doing the number of different lifts to match the lifter’s age.

He geared up to do 60 different lifts. Then he was successful – with many efforts that would have been national records had “Lift Your Age” been sanctioned by the governing body that approves such events.

Now he’s building a neck-lifting harness to go after the national record in the United States All-round Weightlifting Association’s national heavy-lift championship, an event that was first held in Clark’s Gym 30 years ago. His goal is break 500 pounds at age 60 – a record for his age in the 95-kg. (209 lbs.) class.

Have you ever wondered about guys like Dave DeForest? Where do they come from, what drives them – and what are their ultimate goals?

Dave is an excellent example of a normal male who enjoys a hobby. He looks and lives and acts like your next-door neighbor – because he is just that. The only difference, his love affair (outside the family) Is lifting heavy things when others his age have different “big boy toys.”

Dave, to be honest, is not the “guy next door,” but he is the guy “at the next farm down the road.”

He grew up in Marysville, Kansas, a community famous for its black squirrels (they are still there), the youngest of three children.

He was a center and linebacker in football, “but not in the class of the Riggins Brothers,” he admits.

John and Junior Riggins were college football stars and John went on to lead the Washington Redskins to the Super Bowl XVII title and to a losing effort in Super Bowl XVIII. His brother, Franklin (Junior), landed a big bonus contract with the California Angels, but vision problems limited his baseball career.

“They were from ‘just down the road at Centralia,’ and from a decade earlier, but every athlete in the area was compared to them – some of us not for long,” Dave admitted during a recent workout in the sauna of Clark’s Gym – which has no air conditioning and faces southwest.

“I also wrestled, but hated cutting weight and really preferred hunting and fishing on the Big Blue River to the wrestling world.”

Dave graduated from Marysville High in 1978, attended Kansas State for two years, then followed his heart to Lawrence and graduated from Kansas in 1982 with a degree in occupational therapy.

He married Kristy Ringen, who grew up in Beattie, a dozen miles down the road from Marysville, soon after graduation from KU and landed in Fulton – where Dave began 37 years as an occupational therapist at the Fulton State Hospital and Kristy taught junior high mathematics at Auxvasse Junior High for 31 years before retiring in 2014 to handle the family’s orchard business. Dave remains a part-time employee in the occupational therapy section.

In 1985, the DeForests bought 14 ½ acres south of Millersburg on Callaway Route J and planted 400 apple trees. They called the place “Cedar Wind Orchard,” because they love to hear the wind through the nearby cedars.

Along the way, they raised three kids – all girls, all scattered today, and all successful. Bridget Aldrich is a manager at Tiger Tots in Columbia; Lindsey Foster is a mechanical engineer in St. Louis: Ashley Pyle is an ophthalmology technician in Ft. Collins, Colorado. Lindsey and Ashley were both power lifters as teenagers.

Dave and Kristi now have three grandkids to keep them sharp, occasionally enlisting Dave as a baby sitter.

Kristi played softball for years and today is active as a pickle ball player. Both she and Dave love fishing the rivers for big catfish and recently landed a 45-pounder from the Moreau River just above where it enters the Missouri River.

They also pick most of the apples from the 400 trees at Cedar Wind Orchard. They share the orchard’s upkeep and the retail business. Dave says he has the responsibility of spraying the trees twice a year, but Kristi handles the sales and bookkeeping. It works.

Sounds like a normal family, enjoying life, the quiet of the country and the grandkids.

So why weightlifting?

Let Dave explain.

“When I was in the seventh grade, my parents bought me a 110-pound lifting set from Montgomery Ward – a six-foot bar with one-inch plates. I loved it. I added plates and continued lifting through high school, working alone at home. No competition, just the thrill of lifting.

“I was involved in intramurals at Kansas State, but didn’t touch weights again until getting settled at Fulton. I started lifting at home, then found the weight room at the Fulton YMCA and continued to train alone – really thriving on self-motivation.

“In 1994, I entered the Show-Me-State Games at West Junior High, my first meet since the K-State intramurals.

“You and Joe Garcia were in charge, so before the next Show-Me Games, I joined Clark’s Gym. I truly enjoyed the next few years, lifting in the Games and in national and international meets in the USAWA. I ran three open meets that drew the Midwest’s top lifters to North Callaway High and to Westminster College and was thrilled to win a silver medal in the world meet in Valley Forge, Pa., in 1997.

“I realized there was more in life than lifting and family responsibilities put lifting on the back burner, but not totally forgotten.

“So here we are today.”

At age 60, Dave is within range of what he did 20 years ago.

His best lifts included a 355 squat at 181 pounds; a 410 deadlift, 220 bench press, 1,275 hip lift, 1,600 harness lift, 590 neck lift, 850 hand-and-thigh, 600 leg press, 365 hack lift, 375 straddle lift, 390 two-barbell dead lift – all done before the age of 40.

Now, at age 60, he’s flirting with those same poundages.

His goal as a lifter? To beat those “bests” of two decades ago.

And Dave adds: “I love the excitement when my mind and my body come together, and I succeed in doing something I had not done before.”

And now you know why normal-looking family men lift weights.