Wilbur Miller November 12, 1932 – August 5, 2020

By Thom Van Vleck

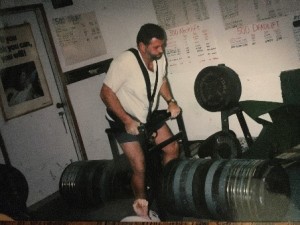

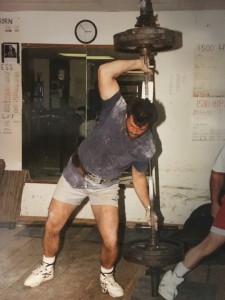

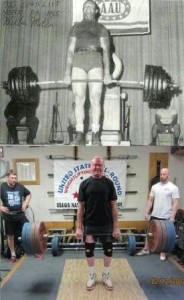

Wilbur was all around strong but he was perhaps most famous for his tremendous Deadlift made all the more impressive with the double overhand grip.

I bring sad news today. The great Wilbur Miller has went to join the other strength greats in the big gym in the sky. To say that Wilbur was a great strength athlete would be an understatement. Here are some of his lifts. Remember, these were in the 60s and Wilbur was a drug free athlete!

Wilbur’s best lifts in competition were: 725# deadlift, 320# clean and press, 320# snatch (split-style), and a 385# clean and jerk. Wilbur often competed in the 240-250 lb bodyweight range. He often gave up over 100 pounds bodyweight to his competitors! His 725 pound deadlift was an World Record at the time, and was done in 1965 in York, Pennsylvania. He weighed 245 pounds in that meet. Even more impressive was that Wilbur had a competitive lifting career that spanned over 50 years! At age 79 he deadlifted 457lbs!

My connection to Wilbur dates back to the 1960s. He and my uncle, Wayne Jackson, had a long standing rivalry on the lifting platform. But off the platform they were the best of friends. When I started lifting as a teen I trained with my Uncle Wayne and he often would tell stories about Wilbur.

Wayne had great respect for Wilbur. Back then in the Olympic lifts they did the Clean & Press before the Snatch and Clean & Jerk. My Uncle Wayne always beat Wilbur on the Clean & Press. But Wilbur, being a very competitive man, would come back and beat Wayne in the Snatch and Clean & Jerk and win the overall. As a kid it elevated my Uncle to hero status in my book that he could best the great Wilbur Miller at anything. It was like throwing a strike against Babe Ruth.

In 1984 I was lifting in a meet in Wichita. My Uncle Wayne came along and we contacted Wilbur. Wilbur came by and hung out all day. He and my Uncle Wayne laughed, told stories, and Wilbur was very polite, open, honest and had little of the ego many lifters of his status have.

The next time I saw Wilbur was about about 20 years later when I did an article on him for Milo. He was still in Medicine Lodge, Kansas with his wife. I stopped by for a visit. You’d think we had been friends our whole lives. He was still training in his garage on a set of York weights from the 60’s. He took me to his “trophy room” and told me stories about each of the mementos, photos, and awards. The whole time he had a smile on his face.

His obituary is as follows:

Wilbur D. Miller, of Wellington, Kansas, passed away on Wednesday, August 5, 2020 at the Glen Carr House in Derby, Kansas at the age of 87.

He was born the son of Howard and Flossie (Brewer) Miller on Saturday, November 12, 1932 in Gray County, Kansas. Wilbur’s grandparents homesteaded the family land and he continued farming the land for many years. On February 5, 1966, Wilbur and Janet (Falkingham) were united in marriage at the First Presbyterian Church in Fredonia, Kansas. Together they celebrated over 54 years of marriage. He was an outdoors-man that enjoyed hunting, fishing and backpacking. Wilbur took up weightlifting as a young man and continued lifting well into his 80’s. He held several national competitive weightlifting records and was a member of the National Weightlifting Hall of Fame. Wilbur loved books and was an avid reader of Louis L’Amour. Additionally, he was a talented musician who taught himself to play the ukulele and harmonica simultaneously and loved to play with his dad and brother. His family remembers him as a great father and grandfather whose calm, steady nature served as the rock of the family. He will be missed by all that knew him.

Survivors include his wife, Janet Miller of Wellington, Kansas; son, William Parker of Tekoa, Washington; son, Robert Parker and his wife Karen of Raymondville, Missouri; daughter, Nancy Fischer and her husband Andy of Golden, Colorado; daughter, Julie Carey and her husband Jeff McGuire of Wellington, Kansas; son, Christoper Miller and his wife Ann of Inman, Kansas, grandchildren: TJ Mensch, Staci Miller Ulrich, Jason Parker, Alexander Parker, Angela Collins, Amanda Ray, Stephen Hoyt, Tricia Halling, Matthew Hoyt, Parker Hoyt, Jeffrey McGuire, Rachel McGuire, Lily McGuire, Kristin Miller, Andy Miller and Anabelle Miller along with numerous great-grandchildren.

He was preceded in death by his parents, Howard and Flossie Miller; brother, Duane Miller and a great-granddaughter, Kennedy Hoyt.

There are many great stories about Wilbur. All show a man with great strength and greater character. I am hoping those who knew him will share one on the message board and we can send them to his family. Additionally, I wrote an article on Wilbur in Milo Strength Journal and if you want a copy let me know. Al Myers wrote a great article on Wilbur that you can find on this website by using the search box.

So take a minute to remember Wilbur Miller. And let’s try to be more like him as well. Strong of body, strong of character.