Strength Through Variety (Part 3)

(Webmaster comment: The following is part of an interesting article written by All-Rounder John McKean several years ago. John has won many All-Round National and World Championships in his weight class, and has written articles for Muscular Development, Hardgainer, Strength and Health, Ironman, Powerlifting USA, and MILO)

by John McKean

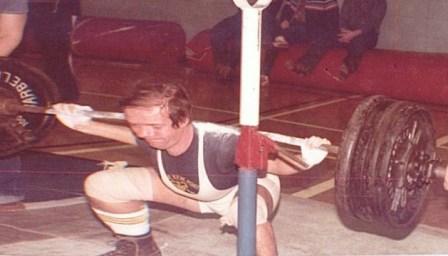

John McKean squatting 530 pounds for a Pennsylvania State Record in 1980. This was done at the Great Lakes Championships in Erie, Pennsylvania in the 148# weight class. John's best competition squat was 555 pounds - before the age of super squat suits!!

“All you need in life is ignorance and confidence, and then success is sure!” stated beloved storyteller Mark Twain. In his famous tongue-in-cheek manner, Twain may have unwittingly provided one of the biggest truths in strength training. For if, as lifters, we envision great success with a highly personalized, unique training pattern, and let our enthusiasm run rampant in its employment, we usually achieve stellar results. Yet, often such a self-styled program is never attempted if those ever-present “experts” are consulted.

Looking back, I suppose my own powerlifting career, which peaked about twenty years ago, could definitely be described as “ignorant yet confident”. Due to a particular fondness for squatting, I naively assumed that some serious specialization on this lift, sustained drive to excel, and very concentrated effort in the gym would allow me to outdo most competitors. Emphasizing mostly brutal, ever-heavier single attempts in training, I actually did manage to establish many local and state records, topping out at 530- and 550-pound bests in the lightweight and middleweight divisions. Heck, it was no real surprise to discover from magazine polls back then that my lifts were even listed among the top ten in the nation for several years. Only later did the shocking truth reveal itself – with my light bone structure (6” wrists), overly long thigh bones, use of neither drugs or supportive gear, and unsophisticated training methods, there was “no possibility” of becoming even mediocre in this event. Man, was I fortunate that nobody told me until it was too late.

My history has provided firsthand education of the absolute value of using a limited program of extremely heavy singles in order to approach one’s maximum power potential. When constantly knocking heads with tiptop poundages, many physical disadvantages can be placed on the back burner. Yet in modern strength literature, noted “authorities” constantly belittle the value of “ones”. Where, I’ve often wondered, did these hardheads come up with the ridiculous “testing strength vs. training for strength” theory which is used so frequently to knock the use of near-limit singles? In actual application, I’ve never seen just such a short, intelligent program fail anybody.

Perhaps many of us master competitors lucked out by starting our training in an age when strength was king – all major bodybuilding and weightlifting moves were keyed toward low-rep, heavy poundages. In the “good old days” we maxed out on everything all the time – and loved it. Our Iron Game heroes, now legends in the sport, regularly utilized short, basic programs which always culminated in several heavy singles. Interestingly, when the renowned Bulgarian national weightlifting team was asked how they developed their “revolutionary” training concept of singling out on all lifts every session, they replied, “from studying the old system of the Americans which we read about in the magazines of the fifties and sixties.”

So, with the advent of modern all-round competition, many of us enthusiastic older trainees already had a tried and true system which easily enabled as many as twenty lifts per week to be worked. Yep, those blessed singles allowed us to spread our energy around while still training with super intensity. Only now, with all-round’s vast array of maneuvers (over 150 lifts which can be contested), we find ourselves using fewer singles per move but making better gains in total body power than ever before, despite our ages being in the forties, fifties and sixties.

A real mental key to deploying a “singles” training schedule is simply to eliminate that word in favor of “a lift”. A near-max lift is certainly about as intense as effort as can be done, yet that low, low number still bothers some. Too many strength trainees today have been constantly brainwashed to the “more is better” concept, even within the context of a set. But, after all, what is a set of, say, eight reps? Simply seven warmups finalized by one tough rep (though with a sub-par poundage compared to a truly heavy single). Why not conserve time and energy by doing a lift with perhaps 40% more weight in the first place?