(Webmaster comment: The following is part of an interesting article written by All-Rounder John McKean several years ago. John has won many All-Round National and World Championships in his weight class, and has written articles for Muscular Development, Hardgainer, Strength and Health, Ironman, Powerlifting USA, and MILO)

by John McKean

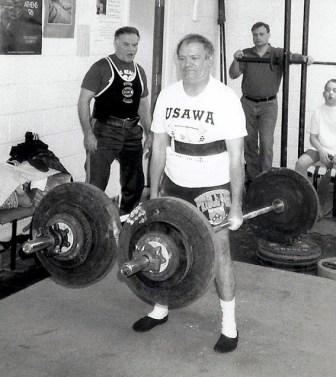

John McKean demonstrating the Jefferson Lift, which is also known as the Straddle Deadlift.

A brief look at weightlifting’s history will quickly show that many of the above-mentioned lifts were the basis of meets during the 1900-1930 era. Rare was it when an early contest didn’t feature a one-arm snatch, dumbell swing, or the amazing bent-press (yes, it’s once again being given its due – number 48 on our all-round list). Extensive record lists on about 50 events were kept in the US and Great Britain prior to 1940, with other informal local listings recorded in both countries during the sixties and seventies.

When serious interest once again picked up, officials from the two lands met in 1987 to write a constitution and promote the new-to-many concept of all-round competition. When these modern day founding fathers established the up to date rules and regulations, they insisted on pure body dynamics to do the lifting – no super suits or supportive gear, no wraps, and absolutely no drugs.

About now, I’m certain many will question the feasibility of training limit poundages on 10-20 big lifts at a time. Doesn’t this go against the grain of current advice to avoid long routines? No. In fact, the real beauty of our all-round sessions is that we’re actually forced to restrict quality training time on each individual lift to an absolute minimum. The necessity of these ultra-abbreviated strength routines has taught us how to reach maximum intensity for handling true top weights more often than ever before.

Although there’s a wide range of effective schedules used by our present crop of all-rounders, and highly specialized methods for handling some of our more unique lifts, here’s a sample training procedure used by 12 of us at the Ambridge VFW Barbell Club, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Essentially, we’ve achieved phenomenal progress over the past five years by doing single repetitions on each of about 6 exercises per workout. We switch lifts every day of our three weekly sessions so that a total of 18 moves are given a short, high-intensity burst once a week. After a special non-weight warmup (more on this later) we do just 3 singles per exercise, best characterized as heavy, heavier, and heaviest. The last attempt is usually fairly close to a limit. And, because this quick, brutal style of training seems to fuel our mental competitive aggression, we always feel motivated to try to up that poundage each week.

Sure, this is heavy stuff. Yet in all our collective time with all-round training, none of us has ever felt even slightly burned out, suffered serious injury, or even felt overly tired from a workout (contests are something else, however). It seems when gains keep coming as rapidly as they have, lifts are always being rotated, and workouts are over before we have a chance of even getting mentally fatigued, our sport always stays fresh, exciting, and ever challenging. After all, how hard can it be to perform a workout of only 18 reps? (Better wait to answer till you actually experience this unique form of intensity and variety).

Most all-round movements are complex by nature and work the entire body at once. Each exercise serves as a supplement to the others, so there’s absolutely no need to waste extra time on assistance exercises. This is also a big reason why we get away with training any particular lift but once a week; all muscle groups are pushed totally each training day, no matter what combination of exercises is employed. After all, why should we bother with, say, the highly overrated and widely overused bench press – very one dimensional when compared to the whole-body functioning of all-round’s dynamic pullover and push.

How well does all-round training serve the average person? Let me offer two rather extreme examples. On a novice level would be my 13-year old son Robbie. Beginning when he was 10, Robbie found immediate pleasure over his rapid strength gains. Thanks to the wide variety of moves and abbreviated training (yes, I put him on heavy singles immediately, despite dire warnings I’ve read by “experts”), he never experienced much muscle soreness nor ever any boredom with his quick workouts. In three years he has gained fifty pounds of muscle (puberty helped), tripled his strength, and has established fifty world records in the pre-teen division.

Recently, while on the way to winning his third consecutive title at 1992’s national championship in Boston, this 165-pound “little boy” performed a show-stopping hand and thigh (short range deadlift). I’ve never seen another youngster of this age who could match Rob’s grip strength to do a 250-pound one-arm deadlift, or the neck power to equal his 300-pound head harness lift. But early in his training, Robbie perceptively put me straight on what this sport is all about. Telling him to follow me downstairs to begin “exercising” one day, he firmly replied, “Dad, I don’t exercise, I lift.”

On the other end of the spectrum is longtime powerlifting and weightlifting competitor, 65-year old Art Montini. As is the case with all of us master lifters, Art discovered that no form of training or competition is as much fun as all-round lifting. Montini never misses one of these exciting workouts and seems to heft new personal bests each time he sets foot in a gym. Who says you stop gaining beyond 35? Art’s name is all over the current record book and he’s never failed to win the outstanding master award at any of our national meets. Seeing the agile oldster deftly upend a 300-pound barbell, twist and stoop to shoulder it then easily squat in the complicated Steinborn lift, or perform his mind-boggling 1,800-pound hip lift would convince anyone that Art drinks gallons daily from the fountain of youth.