Longstrength, Peak Power: Warming Up Chapter 4

by John McKean

Chapter 4 – A Sample Program

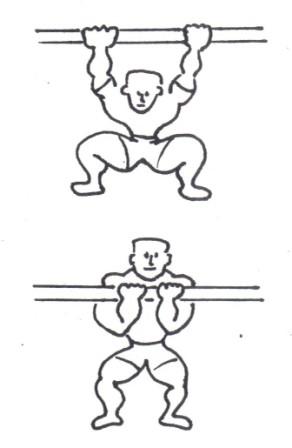

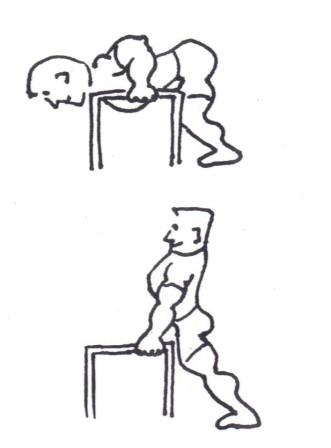

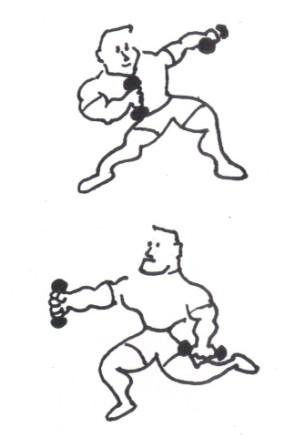

Let’s have you sample a Longstrength warmup followed by a brief, intense barbell routine. Prepare to be amazed at the ease and enjoyment of a truly efficient strength building system. First, grab the lightest pair of barbell plates around for about 12 minutes of shadowboxing. Start very light and easy, both weight-wise and time-wise, for your first session. Don’t be static, but “get into it”—pretend you’re kung fu champion of the world defending against a large dreaded street gang, and wipe ’em all out! Then go to a bar sitting across, a squat rack and rapidly knock out about 60 squat pulls. Finally, with still no rest, locate low dipping bars (or use the back of two chairs) and do a forward bend (also called a “good morning”) between them, pushing back up with combined effort from the arms and lower back. Do these “sissy dips” for 60 reps, and your pre-lift preparation is complete.

By now you should be warm and feeling really good about yourself—after all, you’ve just won a major war and set new personal records for pull-ups and dips! So growl a little bit more, and take, say, 75% of what is estimated to be a “comfortable” best barbell press for this day. Delight in the ease with which you single it up. Rest briefly, then do a single with 85%, and a final lift with 95%. Never missed all the lighter barbell sets, did you? But if you desire some repetitions, now is the very best time for them anyway—back down to 70% and do what will be a very easy 5-8 reps. Follow the same procedure (don’t repeat the warmup, of course, as it will carry you right on through if your barbell workout is brief and intense, as it should be) with the high pull, then the squat. Next workout, follow the same warmup (add half a minute to the shadowboxing and a few more squat pulls and good-morning dips) but do -three different lifts for more varied all-round work.

Your routine looks like this:

MONDAY

Longstrength

- Shadow box: 12 minutes

- Squat Pulls: 60 reps

- Good-morning dips: 60 reps

Lifts

- Press from rack: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6/70%

- High Pull: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6/70%

- Squat: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6/70%

THURSDAY

Longstrength

- Shadowbox: 12 1/2 minutes

- Squat Pulls: 65 reps

- Good-morning dips: 65 reps

Lifts

- One-arm dumbbell press: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6/70%

- One-arm dumbbell row: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6, 70%

- Deadlift: 1/75%, 1/85%, 1/95%, 6/70%

A word about cycling, progression and the rep scheme. As noted in my previous articles in HG, it’s best to base workout percentages on the peak lift for the day, but during the first week of the program this is never a top-ever, personal max. More in the neighborhood of 85% of your very best, with small weekly progressions of 2-1/2 or 5 pounds throughout the cycle. Yes, each cycle will guide you beyond your previous top weight, if you keep at the cycle long enough!

The back-down set

The 70%-rep set after heavy singles adds a degree of very satisfying muscle stimulation. Emotionally, too, it serves as a tremendous “mild pump” because, following the intensity of heavy lifting, it can be performed with complete confidence due to an amazingly “light” feel to the body, and in the perfect form enforced by the just-previous concentration on limit attempts.

In my early powerlifting days, for instance, I always found it a “stroll in the park” to do the backdown set in my squat sessions with 405 pounds for 6-8 reps after singling up to 515-600 pounds. Yet whenever I tried to just work up to that 405 weight and reps on its own (without heavier singles done first), it was an all-out strain and usually a mental and physical impossibility. In retrospect, I suppose it was these down-sets which provided the unexpected result of supplying me nearly 27″ thighs at 5’3″ and about 170 pounds bodyweight—quite a bit overdone size wise, in my opinion, but muscular gains I’ll wager could never have been achieved on my small bone frame with a standard high-rep, high-set pyramid scheme.

Exercises

Keep the exercises basic, ‘breviated, varied and safe. Those listed are fairly standard to most programs, but perhaps a few extra comments are in order.

The one-arm row has always given me the ultimate in lat exercise and is fairly safe compared to the two-arm version, if the non-exercising arm is braced on a bench. Pull smoothly and in good form, yet a bit of extra body heave won’t hurt now and then when poundages get up there. Likewise, the one-arm dumbbell press can recruit more of the body into action while permitting the arms to handle an increased weight (total) over what could be done with the two-arm variety.

The high pull is a total-body movement, starting as a quick deadlift, and accelerating into a high heave toward the chin from mid-thigh level (it’ll probably only reach a little above belly button level with really heavy weights). Form is not super important here, just strive to keep the bar in close to the body, and relish the power you experience when almost all major muscle groups are working coordinately.

Longstrength details

Please don’t overlook your Longstrength progression, however. Always add a few reps to the squat pull and good-morning dip each workout. You really want to get to the stage where minutes are being counted rather than reps. Doctor Tom Auble, a researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, tested these movements extensively and determined that even at a relatively slow pace of 20-30 reps per minute, the workload on squat pulls, for example, done for time, exceeds that of almost all standard aerobic programs. For the lifter, an eventual 6-12 minutes of each maneuver will add superb conditioning to the body along with an unmatched warmup.

Remember always to move from one Longstrength exercise to the next without resting, in contrast to the weight exercises which benefit from 3-5 minutes of rest between sets. The desire is to achieve a steady (but accelerated) heart rate while exercising for a good length of time. While growing familiar with these new applications of strength-orientated exercises (chins, dips, squats, good mornings) a trainee quickly builds into one consistent, steady endurance session. As Dr. Schwartz recently explained to me, “Longstrength offers the enthusiastic trainee maximum torque (a relatively new term referring to mechanical work with subsequential oxygen uptake and calorie expenditure) per pound of bodyweight.”

More than likely, you’ll feel your actual weight lifting in this program is over before it begins, but I guarantee you’ll love the results. Strength gains will come like never before, that nagging tiredness will be replaced with an inner glow, and the old body will display brand new bumps and cuts.

Put in a proper time frame, a really effective warmup will take an enjoyable 20 minutes or so, with perhaps a mere 4 minutes devoted to actually lifting (not counting rest between sets, of course). Never get this 5 to 1 ratio backwards! You see, many of the keys to strength, fitness, and body development can be found in the warmup.